This is the second part of my Blog on the removal of tarnish from silver jewellery. Please click here to read the first part (Number 10)

In the previous part (1) I gave a brief overview of the element silver, what tarnish is and how it occurs and I looked at two methods of removing tarnish: by using an impregnated polishing cloth and by using a chemical solution, or silver dip.

In this second part I will be looking at two further methods. The first one is an interesting process that can be done easily at home with baking soda/washing soda, hot water and aluminium foil and various recipes can be found online.

Electrochemical process (Sodium Bi/Carbonate and Aluminium Foil)

In this process, a ceramic bowl is lined with aluminium foil and a solution of baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) or washing soda (sodium carbonate) and hot water, into which the tarnished piece is submerged. I did experiments with both sodium bicarbonate and sodium carbonate and did experiments to find out for well both works.

“The process is electrochemical, with the carbonate solution acting as the electrolyte. As long as contact is maintained between the two metals, the aluminium corrodes and hydrogen gas is produced. This gas then reacts with the tarnish, reducing it back to the silver metal.”[1]

The object of my experiments was to find how I could remove tarnish from textured surfaces, pieces with a satin finish and those with Keum-Boo patterns.

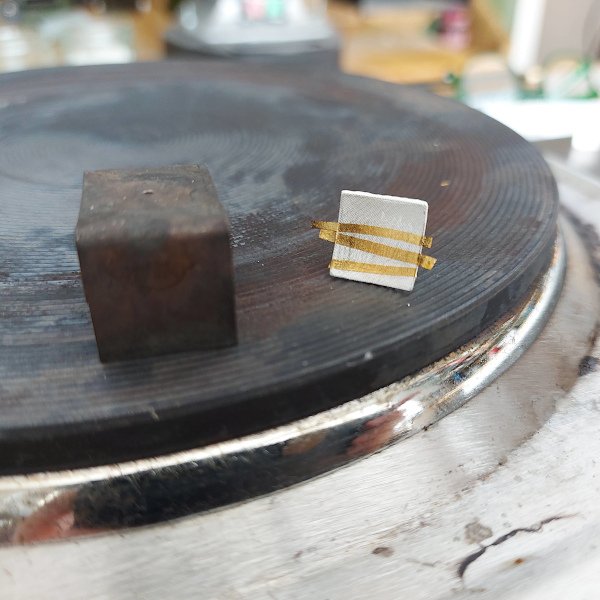

I tarnished a few silver test pieces with the boiled egg method[2]. All silver pieces had a deep, dark-brown tarnished surface. These pieces were also textured, some lightly, some more heavily and some also had 24ct gold Keum-Boo gold patterns.

I lined a ceramic bowl with aluminium foil, added circa 300ml hot water and then a table spoon of sodium bicarbonate / sodium carbonate. I placed the tarnished pieces into the solution and left it for 10 minutes. After this period I lifted the piece out and rinsed it with ionised water.

One can see a brownish rim on the aluminium foil in the bowl which is the removed tarnish.

Baking Soda (Sodium Bicarbonate)

This solution worked well for lightly tarnished surfaces, but it struggled with tarnished pieces that had a deeper brown colour. Even after repeating the process with fresh solution was the tarnish not completely removed.

Washing Soda (Sodium Carbonate)

In the experiment using sodium carbonate I used three pieces I had used in previous tarnish removal experiments as well as one ‘new’ one. All pieces were tarnished with the boiled egg method (see footnote 2) and had a deep brownish-black colour. They were left in the sodium carbonate solution for 10 minutes. After this period most of the tarnish was removed from the ‘new’ piece, whilst the other three still showed quite a bit tarnish.

In summary, this process works well for lightly tarnished pieces, or as a first step of removing some tarnish, to then be followed up by a second method.

Washing soda (sodium carbonate) is a substance that occurs naturally and its safety data sheet classes it as not dangerous for the environment, indeed it is often used as an eco-friendly cleaning agent in the home. Despite this, care must be taken when using it as it can be an irritant for hands and eyes.

Baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) works similarly to washing soda and it is also considered a very safe, biodegradable and eco-friendly cleaning agent.

Other Methods: Precipitated Calcium Carbonate

When researching this subject I came across various documents online published by the Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI). These dealt with different processes of removing tarnish from museum objects and were very thoroughly researched papers and very valuable for this blog.

These papers explained in detail the various aspect on how tarnish occurs, how it can be prevented and how it can be removed.[3]

In relation to removing tarnish it also mentioned another method which falls into the first category of using mechanical action. The substance used here is precipitated calcium carbonate – super-fine chalk (CaCO3).

The article explained, amongst other things, that silver sulphide (tarnish) is a somewhat softer than the actual silver and that calcium carbonate is slightly harder than silver. This make it an ideal and still very gently abrasive to use to remove tarnish.

What is Precipitated Calcium Carbonate (PCC)?

Calcium carbonate (chalk) is a naturally occurring substance. “It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor.”[4]

“Precipitated calcium carbonate (PCC) is an innovative product derived from lime, which has many industrial applications. PCC is made by hydrating high-calcium quicklime and then reacting the resulting slurry, or ‘milk-of-lime’, with carbon dioxide. The resulting product is extremely white and typically has a uniform narrow particle size distribution. PCC is available in numerous crystal morphologies and sizes, which can be tailored to optimize performance in a specific application.”[5]

Is PCC eco-friendly?

The Safety Data Sheet by Thermo Fisher Scientific, one of the companies selling this product, states that PCC does not pose any health or environmental hazards.

As the chalk is a very fine powder care should be taken not to inhale the dust, but as it is mixed with water this risk is somewhat reduced. Rubber gloves should be worn when using it as the powder is abrasive on the skin.

How is it used?

PCC is mixed with tap water to make a paste and is then rubbed over the tarnished surface with a soft cloth.

The substance will turn greyish and it should then be rinsed off with clean tap water. Afterwards the piece should be thoroughly dried.

Results:

I made a paste as described above and used it on some of the above-mentioned tarnished pieces on which the sodium bicarbonate/carbonate and aluminium solution did not fully remove the tarnish.

The calcium carbonate worked very well on all the test pieces. It removed the tarnish completely. The pieces became slightly shinier after the treatment but the surface felt whiter - in comparison to using a polishing cloth.

None of the methods used above were able to retain a previous matte surface finish on the piece.

I contacted the CCI to find out about any specific methods of removing tarnish from matte surfaces. They replied saying that they had no methods of removing tarnish and preserving the matte original surface finish of a piece.

Conclusion:

Removing tarnish from silver can be done in various ways. In terms of their environmental impact or hazardous nature, the most hazardous is the silver dip.

Using a polishing cloth, sodium bi/carbonate and calcium carbonate are low impact methods of removing tarnish, however they may differ in their effectiveness.

Lightly tarnished objects can be cleaned by using polishing cloths or the sodium bi/carbonate, aluminium foil method. For more stubborn tarnish precipitated chalk is a good way of removing tarnish.

I have not found a method of removing tarnish from matte surfaces whilst preserving the matte finish. The matte surface finish would have to be re-applied after tarnish removal. For the customer, those pieces of jewellery should best be given to a jeweller who can restore the previously matte surface finish.

I hope you have found these two blogs interesting. Do let me know if you have any comments.

[1] (Silver – Care and Tarnish Removal – Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI), Notes 9/7, (2019) https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/conservation-preservation-publications/canadian-conservation-institute-notes.html )

[2] As hard-boiled eggs contain and release hydrogen sulphide, they can be used to tarnish objects quickly. Though it is less predictable, it is an eco-friendly way to darken pieces of jewellery. All pieces developed a speckled brown hue which may have been due to the condensation of water inside the closed box.

[3] See footnote 1 above.

[4] Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chalk

[5] https://www.lime.org/lime-basics/uses-of-lime/other-uses-of-lime/precipitated-calcium-carbonate/